By [Olusegun Ogunkayode]

When the People’s Democratic Party (PDP) was given birth to in 1998, it carried itself like the natural party of government. It emerged from the rubble of military rule as a grand coalition of retired generals, old political warhorses and pro-democracy activists who had fought for the return of civil rule.

By 1999, the newly born party had captured Aso Rock, secured a firm grip on the National Assembly, and taken control of a majority of state governments. For 16 unbroken years, the PDP dominated Nigeria’s political landscape like a colossus.

Yet, within that impressive years, fault lines were quietly spreading. What befell the PDP was not a sudden collapse, but a slow political earthquake, triggered by elite arrogance, weak internal democracy, and battles over zoning and power rotation that the party never fully resolved.

Thus is the story of how the “big umbrella” began to leak. The Big-Man Coalition: Seeds of Trouble (1998–2003):- The PDP’s foundation was its first strength and its first weakness.

The party was built as a broad alliance of powerful individuals rather than a disciplined ideological movement. Retired military rulers, influential businessmen, regional power brokers and veteran politicians flocked under its umbrella. The goal was simple: secure power and stabilise the nascent Fourth Republic.

But behind the scenes, godfatherism and imposition of candidates quickly became routine. Party primaries and congresses often took the shape of coronations, not contests. The centre, particularly the presidency, held enormous sway over who got tickets, who became party officials, and who controlled state structures.

The PDP won massively in 1999 and again in 2003, but the foundations it laid were those of a dominant, not a democratic, party. It had the votes, but it did not build consensus or internal discipline. The cracks were beginning to manifest, even if hidden by electoral landslides.

Obasanjo, Power and the Third-Term Shadow (2003–2007):- Under President Olusegun Obasanjo, the PDP consolidated its dominance. The 2003 elections extended the party’s reach, even as opposition parties cried foul over irregularities.

Inside the PDP, Obasanjo gradually tamed many of his internal rivals. Governors who resisted were cut down to size through party sanctions, impeachments, or outright political marginalization. Loyalty to the president, rather than loyalty to party rules, became the surest route to survival.

The most controversial move of this era was the alleged third-term agenda, though widely denied by former President Olusegun Obasanjo. Efforts to amend the constitution to allow Obasanjo seek another term in office divided the PDP elites. Though the project ultimately failed at the National Assembly, it left deep scars of mistrust. Key northern and southern power brokers never forgot that attempt to stretch power beyond agreed limits by the constitution.

The PDP survived the third-term crisis, but its internal cohesion had taken a blow. The party’s barons were now wary of one another and of the presidency.

Zoning, Yar’Adua’s Death and Jonathan’s Emergence (2007–2011):- To manage Nigeria’s fragile balance, the PDP adopted an informal zoning and rotation arrangement: power would shift between North and South, and key party offices would be shared regionally.

In 2007, the party picked Umaru Musa Yar’Adua from the North-northwest while Goodluck Jonathan from the South-South served as his Vice-president, in line with this understanding. The election was widely criticized, but the PDP remained firmly in charge.

Then tragedy struck. In 2010, Yar’Adua died in office after a prolonged illness. Vice President Jonathan, as mandated by the constitution, became president.

For many within the PDP, especially in the North, Yar’Adua’s death did not mean the North’s “turn” had ended. They expected that the party would still field a northern candidate in 2011 to complete the “northern slot.” Jonathan’s decision to run in 2011, and the party’s decision to back him, were seen in some quarters as a breach of the zoning understanding.

Jonathan won the PDP primaries and then the 2011 presidential election. But the victory came at a cost: the party’s support in parts of the North weakened considerably, and feelings of betrayal simmered below the surface. Zoning, once a stabilizer, had become a source of resentment.

Rebellion in the Ranks: The “New PDP” Crisis (2013–2014):- By 2013, the accumulated grievances inside the PDP finally exploded into open rebellion.

At a special national convention in Abuja, a group of influential governors and party leaders staged a dramatic walkout. They announced the formation of a parallel faction, the “New PDP” (nPDP). Amongst them were some of the party’s most powerful governors and figures who had once been pillars of the PDP establishment.

Their complaints were familiar:-Overbearing national leadership, alleged marginalization of certain blocs, poor internal democracy, and deep suspicion that President Jonathan would seek re-election in 2015 against the spirit of zoning.

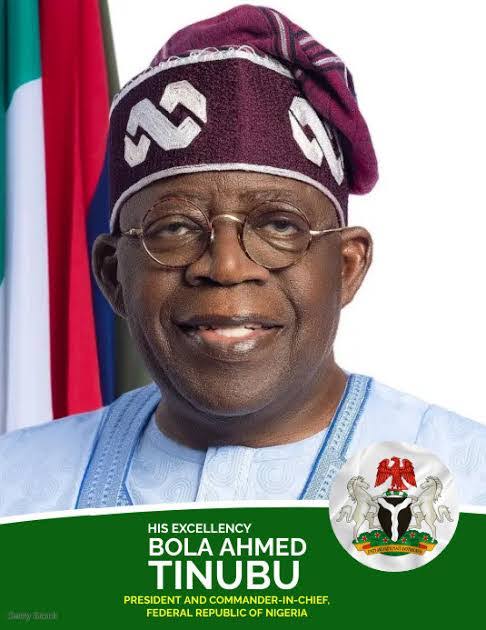

What made the nPDP revolt truly consequential was what followed. Many of its leaders defected to a rising coalition of opposition parties that eventually coalesced into the All Progressives Congress (APC). For the first time since 1999, the PDP faced a united and formidable opposition with ex-PDP stalwarts at its core. The party was bleeding from its own arteries.

The 2015 general elections marked a historic turning point:- Despite holding the advantages of incumbency and national spread, the PDP entered the race internally weakened. Years of internal quarrels, defections, and zoning disputes had taken their toll.

When the votes were counted, the unthinkable happened: President Goodluck Jonathan lost to Muhammadu Buhari of the APC. The PDP’s 16-year grip on the presidency was broken. The party also lost governorships and parliamentary seats across the country.

To Jonathan’s credit, his concession phone call to Buhari helped prevent post-election chaos. But for the PDP, it was more than just a transfer of power; it was the beginning of an identity crisis. A party that had never learned how to be in opposition was suddenly thrown into the cold.

Chairman vs Chairman: Courtroom Politics (2015–2017):- Instead of using the defeat as an opportunity to reform, the PDP descended into a fresh round of leadership tussles.

The most dramatic of these was the battle between Ali Modu Sheriff and Ahmed Makarfi. Sheriff, brought in as a compromise national chairman, soon became the centre of controversy. A rival camp of party leaders rejected his leadership and rallied behind Makarfi, leading to parallel conventions, separate meetings, and conflicting court orders.

For months, the PDP operated like two parties in one, each with its own headquarters, spokesmen and structures. It took a Supreme Court judgment in 2017 to finally affirmed Makarfi’s caretaker committee as the legitimate leadership.

By then, valuable time had been lost. While the ruling APC was consolidating power, PDP was tied down in legal and internal battles over who should control a weakened shell.

Recycling Old Wounds: Atiku, Zoning and the G-5 Drama (2018–2023):- In 2018, seeking to rebrand, the PDP organized what many observers hailed as a more open presidential primary in Port Harcourt. Former Vice President Atiku Abubakar emerged as the party’s presidential candidate for the 2019 election. He lost to Buhari, and once again, the party was forced to lick its wounds.

As 2023 drew nearer, the questions that had haunted the PDP for years returned: Who should get the presidential ticket? Should zoning to the South be enforced? Should the party stick with familiar faces or embrace new ones?

The party chose another open contest. Once again, Atiku clinched the ticket. This time, the fallout was even more severe.

Rivers State Governor Nyesom Wike, who came second in the primaries, felt betrayed and sidelined. He found allies amongst four other governors. Together, they branded themselves the G-5 or Integrity Group. Their demand was simple: if the presidential candidate is from the North, the national chairman should step down for a southerner, in line with the party’s balancing tradition.

The then national chairman, Iyorchia Ayu, did not resign. The rift widened. In the 2023 presidential election, the PDP went into battle with a divided house. Some of its own governors openly or quietly worked against Atiku’s presidential interest. The result was predictable: the party fell short again at the national level and lost more ground in key states.

Today, the PDP remains a major force in Nigerian politics, controlling some states, holding seats in the National Assembly, and retaining a recognizable brand. But it is a shadow of the all-conquering machine that once boasted it would rule for 60 solid years.

What looks like set-back for PDP is not a mystery. It is the story of:- A party built more on personalities than principles, internal democracy repeatedly sacrificed on the altar of imposition and godfatherism, zoning and power rotation agreements observed in the breach, not in the spirit, leadership tussles resolved by court judgments instead of party consensus, and a failure to renew its ranks and reconcile its factions after major defeats.

For Nigeria’s democracy, the PDP’s journey offers a stark lesson: dominance without discipline is a fragile thing. A party can win elections for years and still be eroding from within.

For the PDP itself, the crossroads is clear. It can either confront its past honestly, repairing its internal culture, enforcing fairness, and embracing genuine reforms or continue to drift as a house permanently at war with itself. The umbrella is still standing, but it is torn. Whether it will be mended or finally folded up is a question only the party’s next choices can answer.